Jake’s Story

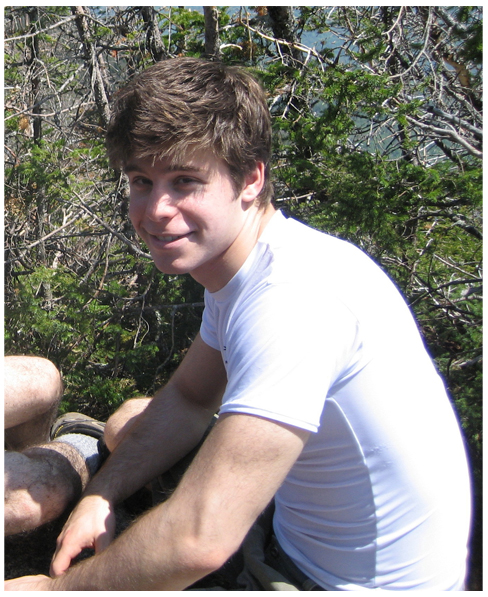

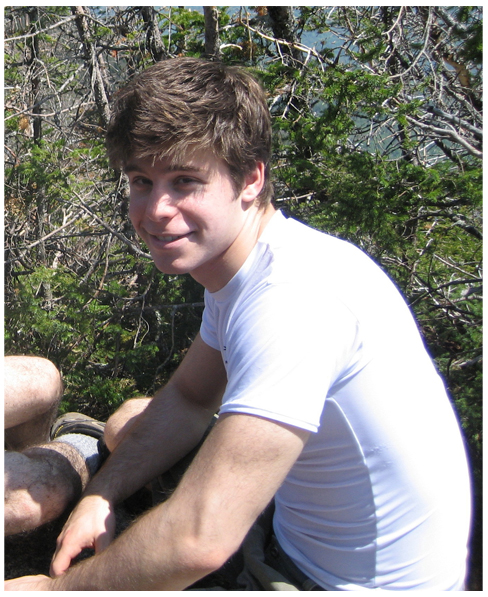

When our son Jake was diagnosed with Hodgkin’s lymphoma, he was in his senior year at Cherry Hill High School East. A born philosopher, one of his favorite quotes was from Nietzsche: “You must become who you are.” At the time, he was busy becoming Jake Wetchler, which meant pushing himself “to the max” as a second-degree black belt in Tang Soo Do and expanding his mind with readings that ranged from Bruce Lee’s teachings in the martial arts to the meditations of Thoreau and the clever repartee of Robert Parker’s Spenser novels. It meant carefully examining his own values and arguing with whomever dared about subjects as weighty as the place of religion in society and, with equal fervor, those as trifling as whether the practice of wrapping gifts should be abolished. To Jake, becoming himself meant standing up for a kid being pushed around by a locker-room bully and intervening persuasively on behalf of a friend about to be disciplined by his parents. It meant building a fire in the wilderness and, as he did on one occasion, chopping down a 30 foot tree with an axe, just for the sense of manly accomplishment. And for Jake, becoming himself meant deliberately challenging the fashion status quo by mixing Abercrombie shirts with ripped up converse sneakers and a leather jacket from Goodwill.

Another part of Jake’s persona was his remarkably deep and resonant voice that prompted people to say, “You should be on the radio” and along with the quick wit that led him to respond with a smile, “What’s the matter, I don’t look good enough for T.V.?” Clever, warm-hearted, and wise beyond his years, Jake never missed the chance to share a grin or a funny quip, and the twinkle in his eye was irresistible. At 18 years old, Jake-the-rebel, Jake-the-joker, Jake-the-thinker, and Jake-the-strongman were all coming together into his own well-centered and spirited self.

Of all the cancers that Jake could have been diagnosed with, the Hodgkin’s was considered a “good” one. Hodgkins has the highest survival rate of all pediatric cancers and the doctors have a well-accepted protocol for treating it. Jake’s disease, however, was classified as Stage IV, meaning that it had spread beyond his lymph nodes to his organs, and the treatment he required was particularly long and aggressive.

Jake, being Jake, fought back against Hodgkin’s with the spirit of a warrior and the soul of a poet. When we sat together in the consultation room at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and the doctors first gave us the diagnosis, he was the one who looked them in the eye and asked, “What are my chances?” The answer was that the odds were in his favor. Still, there were no guarantees—this was cancer—and later that day, after we were taken to Jake’s room on the oncology floor, his father and I (Jake’s mom) stood by his bedside with long faces, searching for the right words to say. Jake picked up a journal he had been keeping and read to us a quote from Moby Dick: “If a man made up his mind to live, mere sickness could not kill him.”

With that attitude, Jake took the offensive against cancer. In the hospital, he insisted on walking into surgery rather than being wheeled and joked with the doctors, “My secret is, I let you guys do all the work.” During one round of in-patient chemo, Jake was given an afternoon of liberty and as we walked out of the hospital together, Jake threw one arm around me and the other around my 200+ pound husband, and—grinning from ear to ear—simultaneously lifted the two of us up into the air. When leaving the hospital after his inpatient treatments, each a three-day-long ordeal, Jake always refused the wheelchair and strode out, his overnight bag slung across his shoulder. Like a prizefighter saluting the crowd as he walks victorious from the ring, Jake would smile as he made his way down the corridors, waving goodbye to the nurses and thanking everyone for their support.

Jake also received outpatient chemo at a local clinic. Following each of these treatments, he and I would drive to his favorite restaurant where he would order an extra-large platter of hot chicken wings, then head home, take a nap and with renewed energy and determination, head to the gym for a weight workout. Jake’s attitude was: “In your face, cancer.”

At school that year, despite frequent hospital stays and confinements to home, Jake wrote and starred in “Joyride Jake,” an award-winning entry in a short film contest; co-anchored the school’s TV news program; took Advanced Placement tests; and applied to colleges, winning scholarships and gaining his acceptances along with the rest of

his class.

The Hodgkin’s treatments lasted Jake’s entire senior year, from September 2007 to June 2008, and that spring we heard the news that made our knees buckle with joy and relief: there was no longer any sign of cancer in Jake’s body. He had beaten back the Hodgkin’s and was officially in remission. The following September, Jake headed off to college, a young man with a passion for the study of philosophy and with the world opening up before him.

Tragically, modern medicine’s cure for cancer is too often a toxic infusion that carries with it the risk of yet more disease. In March of 2009 when Jake came home for spring break, we went for a routine blood test and found that his platelet level was suspiciously low. After a month’s worth of testing we learned, to our horror, that Jake now had AML, acute myeloid leukemia. AML is not a “good” cancer; rather, it is one of the ugliest and most relentlessly aggressive, particularly when it comes as a secondary disease. In all likelihood, Jake’s AML was caused by the chemotherapy used to treat his Hodgkin’s. He received large doses of a drug called etoposide, which has a known association with secondary acute leukemias. Jake described chemotherapy as “medicine that is supposed to kill me, just not all of me.” We need no more poignant example than Jake’s to illustrate that even for ostensibly “treatable” cancers such as Hodgkin’s, the existing chemotherapy regimens and the current “standard of care” is at best a stop-gap measure that in too many cases fails to protect those we love most.

The survival rates for AML were not encouraging: they sat in the vicinity of 30% for secondary AML patients. My husband Jon and I responded by saying that the statistics didn't matter. Even if the chances were just one in ten, we can be – no, we will be, and will do whatever it takes to be – in that winning percentage. People beat it. Why not us? We told Jake that we had every edge possible: the finest medical care, dedicated and loving family, and unbeatable determination.

Jake in the eyes of his peers:

“He would always greet me with a big smile and a firm handshake that reminded me how strong Jake was, not only in muscle, but in spirit, too. I felt stronger just being around him.”

“I remember when I was a very little, defenseless freshman and you had weight room when I had gym, and while I was changing, some big scary guy took my bag with my clothes in it and I tried to get it back from him but he was all big and scary and I was all short and shrimpy and you…just walked up to him, gave him the dirtiest look and were like ‘give. it. back.’ You were my hero.”

“Jake Wetchler once experienced an awkward moment…just to see what it felt like.”

“I know so many people who love to talk and have nothing to say, and every word out of this guy’s mouth I wanted to record so I could reference it later on.”

“You always had some sort of higher wisdom.”

“You weren't just physically strong- you were strong in your convictions, comfortable in your own skin, as you walked proudly down the hallway...”

“The way you would always challenge every ideology you didn't believe in wholeheartedly really was inspiring.”

“I have never looked up to someone my own age as much as I looked up to you.”

“The sweet, wholesome gentleman underneath the ‘I am a manly man!’ exterior…you squeezed out every ounce of life you were given with the remarkable strength you possessed.”

“When you entered a room everyone knew you were there because the presence that you gave off.”

“You were a person who could bring light to even the darkest of places.”

“The voice of gold…you touched more lives than you know.”

Jake, characteristically, refused to accept our unfettered optimism and insisted on having the truth laid bare. When Jon said to him, “I know we can win, I know we can beat this,” Jake responded: “How do you know? Are you a god? Can you predict the future?” Jake was unwilling to indulge in blind optimism or self-deception in exchange for personal comfort. After heated discussion among the three of us, he concluded that if this battle could be won by anything that is humanly or medically possible, then we would win—but that whether in the end he lived or died depended on forces beyond his control. Jake did not, however, need an assurance of victory in order to fight with unrelenting will. He faced cancer with illusions pushed aside, and his insistence on clarity and honesty set the ground rules for a fight on his own terms.

Jake knew the odds were against him, but he also knew that he got to choose—not his ultimate fate, but his attitude in responding to whatever situations life threw his way. Jake’s choice was to fight back against cancer with the same humor, strength, style, and “stick it to the man” attitude that characterized his life, never forsaking the grin and the wink, the uncompromising love of argument, or the unerring sense of irony that made him who he was. In words he wrote in his journal:

“…though I might die tonight, I must plan on fighting for tomorrow. Fear is real and right, but must be confronted and sometimes conquered if it gets in the way of living. I must embrace my fear, for it is here for a reason—but I must not let it stop me. It will make me stronger. I will love life better. I have the chance to fight nobly. I will go to sleep, and wake up tomorrow knowing that a battle has been won, and there is a full day ahead of me for celebration.”

We had thought the chemo for Stage IV Hodgkins was tough but compared to the treatments for AML, it was minor league. Nonetheless, despite one surgery after another, unrelenting nausea, radiation that burned his skin from head to toe, and the dreadful side effects that occur when chemotherapy assaults not just the cancer cells but the healthy, fast-growing cells throughout your body, Jake never wavered in his determination and never complained. In fact, just the opposite, he always found a way to bounce back, to buoy his spirits, and face the battle head-on once again.

In the hospital, during our month-long stays, Jake requested a mat for his room so he could do push-ups. After his first round of chemo and a devastating lung infection that landed him in the Intensive Care Unit on a breathing machine, Jake fought his way back to doing 30 push-ups, 20 on his knuckles. We carried in free weights and an exercise bike from home, and Jake’s hospital room began to resemble a small gym.

Whoever walked into Jake’s room was greeted with a smile, a “c’mon in” and, if they were lucky, one of Jake’s inimitable quips. Typical of these was the way Jake would kid with the nurses during a shift change. The new nurse would come in and say, “"Hi, I'm Celeste and I'm going to be your nurse", to which Jake would reply, "Hi, I'm Jake and I'm going to be your patient." Everyone would smile.

Jake challenged hospital convention when he felt the rules unjust or the treatment undignified. For example, one night he called room service and they put him on hold for an interminably long time, an offense he took personally. After placing his dinner order, he hung up and then called them back. When the attendant picked up, Jake said, “Can you hold please?” and proceeded to sing into the phone, his face alit with the satisfaction of justice served. Five minutes later, a bewildered attendant asked, “Mr. Wetchler, is that you?” Jake gave his best but demanded it in others as well, and beware to the young resident who might saunter into his room to announce treatment instructions without his or her facts in order. Jake would grill them relentlessly until he was given answers that were logical or until the resident backed out of the room to go find someone more senior.

With round after round of chemo, Jake and his doctors would beat the cancer back. But just as reliably, every time it looked like the cancer might be in retreat, and regardless of how hard Jake fought to breathe and eat and exercise in order to regain his strength, the cancer returned. Our medical care was the best available. We had outstanding doctors who were experts in their field and every day showed heart-felt dedication and concern for Jake and for us as his family. Jake was treated at two of the preeminent cancer institutions in the country. The tools they had to fight AML, however, were woefully inadequate and failed to eliminate the cancer at its source. After a stem cell transplant, Jake fought his way back from debilitating complications and was proudly walking laps around the hospital corridors—but once again, the cancer returned. The doctors had exhausted all their medical options and shortly afterward, Jake passed away.

In our hospital room during the spring of 2009, when we were just starting Jake’s AML treatments, we hung a big poster of Rocky in the gray of a Philadelphia dawn with his arms outstretched and a somber look on his face that said, “This is going to be tough as hell and I’m going to get battered and bloodied, but I will never stop fighting.” That poster traveled with us from room to room and hospital to hospital. Like Rocky, Jake’s mind was set on “going the distance.” In many ways, Jake’s story has a tragic ending. But while cancer killed Jake, it never defeated him. Jake went the distance, and more, and his story is one of an indomitable spirit. In his honor, and in our continuing fight against cancer, that spirit is ours.

Jake’s Story

When our son Jake was diagnosed with Hodgkin’s lymphoma, he was in his senior year at Cherry Hill High School East. A born philosopher, one of his favorite quotes was from Nietzsche: “You must become who you are.” At the time, he was busy becoming Jake Wetchler, which meant pushing himself “to the max” as a second-degree black belt in Tang Soo Do and expanding his mind with readings that ranged from Bruce Lee’s teachings in the martial arts to the meditations of Thoreau and the clever repartee of Robert Parker’s Spenser novels. It meant carefully examining his own values and arguing with whomever dared about subjects as weighty as the place of religion in society and, with equal fervor, those as trifling as whether the practice of wrapping gifts should be abolished. To Jake, becoming himself meant standing up for a kid being pushed around by a locker-room bully and intervening persuasively on behalf of a friend about to be disciplined by his parents. It meant building a fire in the wilderness and, as he did on one occasion, chopping down a 30 foot tree with an axe, just for the sense of manly accomplishment. And for Jake, becoming himself meant deliberately challenging the fashion status quo by mixing Abercrombie shirts with ripped up converse sneakers and a leather jacket from Goodwill.

Another part of Jake’s persona was his remarkably deep and resonant voice that prompted people to say, “You should be on the radio” and along with the quick wit that led him to respond with a smile, “What’s the matter, I don’t look good enough for T.V.?” Clever, warm-hearted, and wise beyond his years, Jake never missed the chance to share a grin or a funny quip, and the twinkle in his eye was irresistible. At 18 years old, Jake-the-rebel, Jake-the-joker, Jake-the-thinker, and Jake-the-strongman were all coming together into his own well-centered and spirited self.

Of all the cancers that Jake could have been diagnosed with, the Hodgkin’s was considered a “good” one. Hodgkins has the highest survival rate of all pediatric cancers and the doctors have a well-accepted protocol for treating it. Jake’s disease, however, was classified as Stage IV, meaning that it had spread beyond his lymph nodes to his organs, and the treatment he required was particularly long and aggressive.

Jake, being Jake, fought back against Hodgkin’s with the spirit of a warrior and the soul of a poet. When we sat together in the consultation room at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and the doctors first gave us the diagnosis, he was the one who looked them in the eye and asked, “What are my chances?” The answer was that the odds were in his favor. Still, there were no guarantees—this was cancer—and later that day, after we were taken to Jake’s room on the oncology floor, his father and I (Jake’s mom) stood by his bedside with long faces, searching for the right words to say. Jake picked up a journal he had been keeping and read to us a quote from Moby Dick: “If a man made up his mind to live, mere sickness could not kill him.”

With that attitude, Jake took the offensive against cancer. In the hospital, he insisted on walking into surgery rather than being wheeled and joked with the doctors, “My secret is, I let you guys do all the work.” During one round of in-patient chemo, Jake was given an afternoon of liberty and as we walked out of the hospital together, Jake threw one arm around me and the other around my 200+ pound husband, and—grinning from ear to ear at the audacity of it all—simultaneously lifted the two of us up into the air. When leaving the hospital after his inpatient treatments, each a three-day-long ordeal, Jake always refused the wheelchair and strode out, his overnight bag slung across his shoulder. Like a prizefighter saluting the crowd as he walks victorious from the ring, Jake would smile as he made his way down the corridors, waving goodbye to the nurses and thanking everyone for their support.

Jake also received outpatient chemo at a local clinic. Following each of these treatments, he and I would drive to his favorite restaurant where he would order an extra-large platter of hot chicken wings, then head home, take a nap and with renewed energy and determination, head to the gym for a weight workout. Jake’s attitude was: “In your face, cancer.”

At school that year, despite frequent hospital stays and confinements to home, Jake wrote and starred in “Joyride Jake,” an award-winning entry in a short film contest; co-anchored the school’s TV news program; took Advanced Placement tests; and applied to colleges, winning scholarships and gaining his acceptances along with the rest of his class.

The Hodgkin’s treatments lasted Jake’s entire senior year, from September 2007 to June 2008, and that spring we heard the news that made our knees buckle with joy and relief: there was no longer any sign of cancer in Jake’s body. He had beaten back the Hodgkin’s and was officially in remission. The following September, Jake headed off to college, a young man with a passion for the study of philosophy and with the world opening up before him.

Tragically, modern medicine’s cure for cancer is too often a toxic infusion that carries with it the risk of yet more disease. In March of 2009 when Jake came home for spring break, we went for a routine blood test and found that his platelet level was suspiciously low. After a month’s worth of testing we learned, to our horror, that Jake now had AML, acute myeloid leukemia. AML is not a “good” cancer; rather, it is one of the ugliest and most relentlessly aggressive, particularly when it comes as a secondary disease. In all likelihood, Jake’s AML was caused by the chemotherapy used to treat his Hodgkin’s. He received large doses of a drug called etoposide, which has a known association with secondary acute leukemias. Jake described chemotherapy as “medicine that is supposed to kill me, just not all of me.” We need no more poignant example than Jake’s to illustrate that even for ostensibly “treatable” cancers such as Hodgkin’s, the existing chemotherapy regimens and the current “standard of care” is at best a stop-gap measure that in too many cases fails to protect those we love most.

The survival rates for AML were not encouraging: they sat in the vicinity of 30% for secondary AML patients. My husband Jon and I responded by saying that the statistics didn't matter. Even if the chances were just one in ten, we can be – no, we will be, and will do whatever it takes to be – in that winning percentage. People beat it. Why not us? We told Jake that we had every edge possible: the finest medical care, dedicated and loving family, and unbeatable determination.

Jake, characteristically, refused to accept our unfettered optimism and insisted on having the truth laid bare. When Jon said to him, “I know we can win, I know we can beat this,” Jake responded: “How do you know? Are you a god? Can you predict the future?” Jake was unwilling to indulge in blind optimism or self-deception in exchange for personal comfort. After heated discussion among the three of us, he concluded that if this battle could be won by anything that is humanly or medically possible, then we would win—but that whether in the end he lived or died depended on forces beyond his control. Jake did not, however, need an assurance of victory in order to fight with unrelenting will. He faced cancer with illusions pushed aside, and his insistence on clarity and honesty set the ground rules for a fight on his own terms.

Jake knew the odds were against him, but he also knew that he got to choose—not his ultimate fate, but his attitude in responding to whatever situations life threw his way. Jake’s choice was to fight back against cancer with the same humor, strength, style, and “stick it to the man” attitude that characterized his life, never forsaking the grin and the wink, the uncompromising love of argument, or the unerring sense of irony that made him who he was. In words he wrote in his journal:

“…though I might die tonight, I must plan on fighting for tomorrow. Fear is real and right, but must be confronted and sometimes conquered if it gets in the way of living. I must embrace my fear, for it is here for a reason—but I must not let it stop me. It will make me stronger. I will love life better. I have the chance to fight nobly. I will go to sleep, and wake up tomorrow knowing that a battle has been won, and there is a full day ahead of me for celebration.”

We had thought the chemo for Stage IV Hodgkins was tough but compared to the treatments for AML, it was minor league. Nonetheless, despite one surgery after another, unrelenting nausea, radiation that burned his skin from head to toe, and the dreadful side effects that occur when chemotherapy assaults not just the cancer cells but the healthy, fast-growing cells throughout your body, Jake never wavered in his determination and never complained. In fact, just the opposite, he always found a way to bounce back, to buoy his spirits, and face the battle head-on once again.

In the hospital, during our month-long stays, Jake requested a mat for his room so he could do push-ups. After his first round of chemo and a devastating lung infection that landed him in the Intensive Care Unit on a breathing machine, Jake fought his way back to doing 30 push-ups, 20 on his knuckles. We carried in free weights and an exercise bike from home, and Jake’s hospital room began to resemble a small gym.

Whoever walked into Jake’s room was greeted with a smile, a “c’mon in” and, if they were lucky, one of Jake’s inimitable quips. Typical of these was the way Jake would kid with the nurses during a shift change. The new nurse would come in and say, “"Hi, I'm Celeste and I'm going to be your nurse", to which Jake would reply, "Hi, I'm Jake and I'm going to be your patient." Everyone would smile.

Jake challenged hospital convention when he felt the rules unjust or the treatment undignified. For example, one night he called room service and they put him on hold for an interminably long time, an offense he took personally. After placing his dinner order, he hung up and then called them back. When the attendant picked up, Jake said, “Can you hold please?” and proceeded to sing into the phone, his face alit with the satisfaction of justice served. Five minutes later, a bewildered attendant asked, “Mr. Wetchler, is that you?” Jake gave his best but demanded it in others as well, and beware to the young resident who might saunter into his room to announce treatment instructions without his or her facts in order. Jake would grill them relentlessly until he was given answers that were logical or until the resident backed out of the room to go find someone more senior.

With round after round of chemo, Jake and his doctors would beat the cancer back. But just as reliably, every time it looked like the cancer might be in retreat, and regardless of how hard Jake fought to breathe and eat and exercise in order to regain his strength, the cancer returned. Our medical care was the best available, we had outstanding doctors who were experts in their field and every day showed heart-felt dedication and concern for Jake and for us as his family. Jake was treated at two of the preeminent cancer institutions in the country. The tools they had to fight AML, however, were woefully inadequate and failed to eliminate the cancer at its source. After a stem cell transplant, Jake fought his way back from debilitating complications and was proudly walking laps around the hospital corridors—but once again, the cancer returned. The doctors had exhausted all their medical options and shortly afterward, Jake passed away.

In our hospital room during the spring of 2009, when we were just starting Jake’s AML treatments, we hung a big poster of Rocky in the gray of a Philadelphia dawn with his arms outstretched and a somber look on his face that said, “This is going to be tough as hell and I’m going to get battered and bloodied, but I will never stop fighting.” That poster traveled with us from room to room and hospital to hospital. Like Rocky, Jake’s mind was set on “going the distance.” In many ways, Jake’s story has a tragic ending. But while cancer killed Jake, it never defeated him. Jake went the distance, and more, and his story is one of an indomitable spirit. In his honor, and in our continuing fight against cancer, that spirit is ours.

Jake in the eyes of his peers:

“He would always greet me with a big smile and a firm handshake that reminded me how strong Jake was, not only in muscle, but in spirit, too. I felt stronger just being around him.”

“I remember when I was a very little, defenseless freshman and you had weight room when I had gym, and while I was changing, some big scary guy took my bag with my clothes in it and I tried to get it back from him but he was all big and scary and I was all short and shrimpy and you…just walked up to him, gave him the dirtiest look and were like ‘give. it. back.’ You were my hero.”

“Jake Wetchler once experienced an awkward moment…just to see what it felt like.”

“I know so many people who love to talk and have nothing to say, and every word out of this guy’s mouth I wanted to record so I could reference it later on.”

“You always had some sort of higher wisdom.”

“You weren't just physically strong- you were strong in your convictions, comfortable in your own skin, as you walked proudly down the hallway...”

“The way you would always challenge every ideology you didn't believe in wholeheartedly really was inspiring.”

“I have never looked up to someone my own age as much as I looked up to you.”

“The sweet, wholesome gentleman underneath the ‘I am a manly man!’ exterior…you squeezed out every ounce of life you were given with the remarkable strength you possessed.”

“When you entered a room everyone knew you were there because the presence that you gave off.”

“You were a person who could bring light to even the darkest of places.”

“The voice of gold…you touched more lives than you know.”